California needs significant reductions in transportation-related emissions to meet its climate targets. Those reductions need to come from both the vehicles themselves as well as mode shift – reducing the number of Vehicles Miles Traveled (VMT). Rail electrification is a policy that accomplishes both goals: it converts diesel-spewing trips to clean electric trips, and it can take both cars and trucks off the road with better transit service. Unfortunately, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) can be a risky and costly barrier to the realization of these projects. This is the first in a series of blogs laying just exactly how CEQA is holding back transformative rail projects.

CEQA background

CEQA requires public projects or private projects seeking discretionary approval from a public agency to evaluate and mitigate the impacts of the proposed project on the physical environment. Projects that fail to adequately analyze and mitigate such impacts are vulnerable to legal challenges that can result in additional analysis or abandonment.

For large infrastructure projects such as freeways or natural gas facilities that are likely to induce greater VMT, greenhouse gas, particulate and/or toxic emissions, and require mass alterations to the natural or built environment, CEQA is a valuable tool for the public to adequately understand these impacts.

Unfortunately, projects that tend to reduce VMT and emissions and require much smaller alterations to the environment, such as bike lanes, bus lanes and light rail projects within existing rights-of-way (ROW) have historically been subject to the same CEQA requirements for lengthy analysis and costly mitigation and legal risk.

For example:

- The San Francisco Master Bike Plan to provide protected bike lanes and traffic calming infrastructure was challenged under CEQA and delayed for years by a single litigant motivated by impacts of the plan on traffic and car parking.

- The threat of a CEQA lawsuit by Berkeley homeowners and businesses concerned about the loss of on-street parking forced AC Transit to abandon plans for its Tempo bus line connecting San Leandro - East Oakland- Fruitvale - Downtown Oakland (now the highest ridership line in the system) to extend up to Telegraph Avenue through North Oakland to the UC Berkeley campus.

In 2020 the legislature recognized that certain lower impact transportation projects such as bike lanes, bus lanes, light rail in existing ROWs, pedestrian infrastructure, removal of parking minimums and on-street parking pricing should be exempted from CEQA – provided they meet certain environmental, anti-displacement and economic standards – by enacting SB 288. In 2022 the legislature reaffirmed this policy by enacting SB 922 to extend, refine, and expand these exemptions until 2030.

CEQA as Applied to Electric Rail

Rail electrification suffers from three primary risks under CEQA.

First, CEQA can tend to increase the costs and timelines of rail electrification projects through increased scope due to mitigation of questionable environmental impacts. The primary drivers of these increased costs are Visual and Aesthetic impacts that must be analyzed under CEQA. Let’s use Visual impacts as an example. Visual impacts are analyzed under a Visual Impact Assessment. These analyses typically use the Federal Highway Administration’s methodology of breaking up the project into discrete viewsheds (places that can be easily seen from the project setting). Each viewshed must be analyzed in terms of “vividness, intactness, and visual unity captured in key views to assess the level of visual quality present, both before and after the proposed Project is implemented.”

The systems of rail electrification, the poles, wires and substations that power trains, are continuous throughout miles of ROW and will end up impacting the “vividness, intactness, and visual quality” of some viewshed.

Once those visual impacts cross thresholds of significance CEQA imposes an obligation to 1) mitigate such impacts to below significance; or otherwise 2) the public agency must declare the impacts unavoidable and unmitigable and pass a resolution of overriding considerations in adopting the environmental impact report.

The latter option is risky because it exposes the public agency to legal challenge by litigants who seek to second guess whether such impacts were unavoidable and mitigation unavailable or infeasible. If the challengers win the public agency would have to re-do their environmental analysis, likely forced into additional expensive mitigation and pay attorneys’ fees. Instead, agencies opt to placate potential opponents early by committing to expensive mitigation from visual impacts.

Mitigation for Electric Rail

What does mitigation look like for rail electrification?

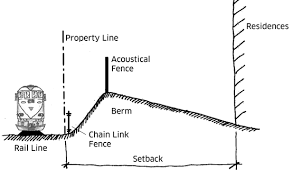

First, the lowest cost mitigation is a simple sound wall or high fence. These require clear rights-of-way, foundations and concrete or metal sidings.

A berm is more expensive. It consists of cut and fill of earth to obscure views of the rail electrification infrastructure. These civil works can be expensive, especially where dirt must be imported due to lack of nearby soil.

Next there are cuttings, which consists of dirt removed from a right-of-way to create berms on either side of the railroad. These soil cuts and their removal create a new set of environmental impacts as soil may need to be trucked and deposited off-site. The increased removal of soil increases the cost as well as the risk that an unmapped utility or unknown object is discovered, which can slow down project progress.

Finally there are tunnels, such as the ones being constructed for HS2 in England to preserve views of rural woodlands. These are massive, costly endeavors that can be performed via cut and cover or tunnel boring machines.

These mitigation options can range from tens of millions to billions of dollars, and they increase construction schedules as they add additional scope, utility relocations, and 3rd party negotiations. They also add operations and maintenance costs to the operating system that cannot be recouped through fares or fees as they do not improve service.

Litigation

Second, rail electrification projects are exposed to delay via CEQA lawsuits (more on this in Part 2), which can delay project delivery and increase costs.

Even if apublic agency has priced in mitigation and approved a strong CEQA document, it can still be sued under CEQA by dissatisfied parties seeking to block the projects. Litigants may earnestly wish to improve projects but just as often they may want to simply stop projects entirely or bleed them dry through predatory delay as funding and political support disappear.

A CEQA lawsuit can delay a project for 2-5 years depending on the wealth and willingness of litigants to exhaust their appeals. In that time, political environments, public budgets, interest rates, labor and material prices may change and render a project that was previously viable, unviable.

Even if a project does proceed after delay via CEQA challenge, and possibly, re-circulated environmental impact report, that delay has pushed back construction and subsequently electrified, zero emission service. That leaves more Californians in their cars and puts more emissions in our local and global environment.

Rail electrification projects that never get traction

Third, the threat of CEQA mitigation costs and legal challenge scares off public agencies from even considering rail electrification. This may be the most impactful risk of CEQA. We’ll do some deep dives into this in Part 3 of this series.

Passenger and freight railroads are risk averse, especially when it comes to their assets like trains and ROW. As demonstrated throughout the globe, modernizing and electrifying rail operations can be a good business decision on higher-traffic lines that speeds up service and reduces operating costs and environmental emissions. But the mechanics of that transition comes with its own risks to operations, revenues and long-term fitness of railroads.

The CEQA process adds even more risk to the business case for electrification. That mitigation will cause scope and costs to spiral. That they will be sued. That the project may be delayed for years and years.

For this reason, mainline rail electrification has not gotten far in California outside of the Caltrain line from San Francisco to San Jose. Agencies are not willing to undergo planning and environmental review processes given the upfront risks.

Caltrans, CARB and others have increasingly turned to speculative technologies with no proven track record and dubious environmental bona fides such as hydrogen multiple units in order to transition to zero emission service. Such technologies have no use case apart from low traffic rural lines, are significantly more expensive to purchase and maintain, and pose significantly higher environmental, carbon and safety risks than rail electrification but do not have the same Visual or Aesthetic impacts.

Clearly our environmental review processes are failing in some aspects when they are resulting in agencies choosing options that are worse for the environment, operations and costs.

Stay tuned for part 2, where we’ll cover how CEQA harmed Caltrain electrification.

0 Comments